By Jonas Bylund, Marcus Adolphson and Tony Svensson, KTH Royal Institute of Technology

By 19 September 2023, we ran the final workshop in a series of seven over 2022–2023. These were set up to explore the collaborative explorative scenario approach in planning practice and what capacities needed to address accessibility and uncertainty. This instalment presents a selection and short reflection on what we found to be the most pertinent insights from the Norrköping shadow planning exercise.

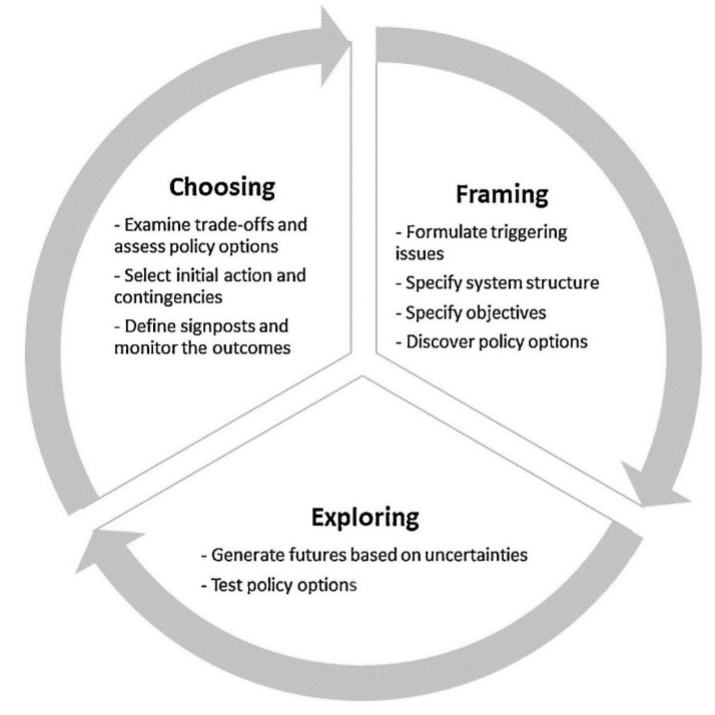

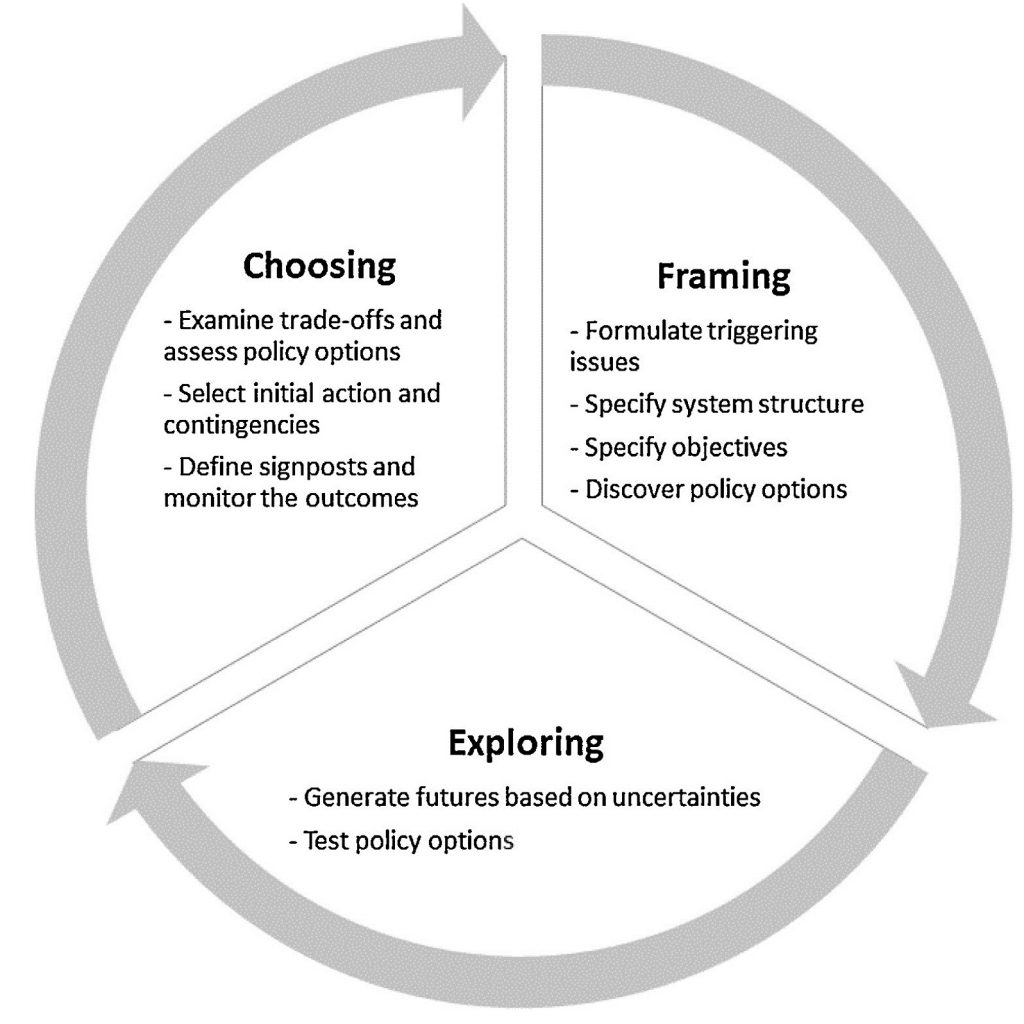

When we talk of accessibility planning here it is in the sense of ‘genuine’ accessibility, i.e. not merely taking person mobility into account but also how to plan land-use and location aspects as well as digital accessibility dynamics emerging in everyday life. the workshop series explored scenarios co-created with Norrköping planners, where accessibility and uncertainties around potential future developments both in the municipality and in society at large was set-up as a kind of policy lab with the intention of probing requirements by planning practice to realise sustainable urban mobility planning (TAP in SUMP; see previous blog posts here and here).

The approach to understand how to assess and build planning practice capacities was, according to Patsy Healey (back in 1998), first thought of as a general issue of enabling and developing capacities for collaborative planning by looking at three dimensions in planning practice: knowledge, relational, and mobilisation. However, these dimensions are useful to assess other issues as well, such as the capacity to plan for accessibility and take uncertainty into account in a planning practice setting.

Healey observed that the increased fragmentation of the European city – which is nowadays understood as a common challenge both in terms of spatial form and place characteristics as well as thematic and sectoral fragmentation (e.g. JPI Urban Europe SRIA 2.0 and the DUT Roadmap) – made sense of place crucial for environmental systems development and for social and economic lives.

Hence, for urban and regional planning to produce, improve, and maintain sense of place, urban governance, i.e. city administrative and urban functional areas wide, require institutional capacities to work across sectoral fragmentation and with complex issues such as integrated mobility, land-use, and digitalization dynamics.

Healey arrived at three dimensions needed to build these capacities:

- Knowledge resources, where knowledge is understood in a wider sense than simply certified (academic) formal knowledge products and including layperson knowledge and learning environments for all actors involved in planning practices.

- Relational resources, in the sense of how the actors are enabled to relate to each other, for instance regarding at what instances in planning processes more open deliberation and reflection together is curated, e.g. addressing agenda setting issues and fending off de-politicisation.

- Mobilization capacities, then, are about institutional responsiveness to new circumstances – since planning is always concerned with a moving target, so to speak.

The hypothesis was originally conceived to support collaborative approaches to place development. (See here for a review of the contemporary field.) However, looking at co-creation and the development of how urban governance is understood during the last 30–40 years – e.g. both the dark sides of public participatory approaches as well as the ontological sense of an omnipresent co-creation, since you can’t do anything without collaboration in some sense – we may interpret it to be a case of how to support institutional capacities for planning and governance in general.

Three observations

With the focus on building capacity and assessing them, we observed issues around knowledge, relational aspects, and mobilisation in the Norrköping case as particularly interesting. What follows are some early signposts on possible conclusions from the workshop series.

Knowledge issues

Since the collaborative explorative scenario approach was seen as helpful to better understand the possible complex interplay of issues in accessibility planning, it added value as suitable for context exploration in strategic comprehensive planning rather than learning the methodology per se. Furthermore, the scenario approach provided a kind of sandbox setting where that interplay could be conceptually experimented with.

However, knowledge on or of ‘accessibility’ was itself an issue. It varies not just among the planners in the workshop but the planners also reflected upon the divergent perspectives on accessibility among other officials, politicians, and stakeholders. The approach can be used to draw together these understandings and knowledge, aligning its bits and pieces, so to speak, which are unevenly dispersed across the different types of actors, and highlight incongruencies.

Regarding knowledge on how to deal with uncertainty, working with the group of planners it becomes clear that ‘uncertainty’ is not an external factor to the local planning context but pervades everywhere – including political power dynamics. While they strive to ‘put them out,’ there is a challenge articulated in a desire have ‘the right things’ left uncertain (or open-ended) and at what stages in the planning process.

Relational aspects highlighted by the approach

It is noted by the planners that the approach may help articulate capacity deficits to take relational aspects into account and may be a good way to widen the scope of the strategy development since ‘one [usually] wants to narrow it down as much as possible’ in order to avoid a too quick-and-dirty planning process.

Relational aspects in accessibility – something which is a tautology perhaps – such as inviting more diverse competencies to widen the planning scope, becomes important as they articulate how many things co-develop and interact in urban planning. A lot of moving parts… Here, of course, uncertainty also seeps in through all relational matter in accessibility to take into account and if addressed in full leads to ‘decision paralysis.’

Mobilisation capacity

The planners reflect upon them being uncomfortable with stating precise goals and targets for e.g. accessibility in the planning process and resulting documents, since this may then direct the development of the whole municipality without due democratic political steering capacity or flexibility. Mobilisation may help work around this, when utilising the collaborative explorative scenario approach, to ‘prep’ and help the governance context to learn – potentially in fora to share the knowledge generated in this approach.

The mobilisation aspect when we trace/assess institutional capacities in planning practice, then, when focusing on uncertainty in the planners everyday work, leads to a speculation on whether a task force – an internal organisation or group tasked to work with scenario approaches – could anchor the tackling/handling of uncertainty better in the public administration, particularly in preparatory and analysis stages.

Policy labs as a way forward?

These observations and reflections has a resonance in some of the results on the workshop series carried out by Mistra SAMS: that there are challenges in integrating the genuine or broader sense of accessibility and digital accessibility is still relatively abstract compared to conventional mobility and land-use aspects.

So, what to do with accessibility, uncertainty, and scenario approaches, then? The TAP handbook to be launched soon will cover some aspects on how to take it further in planning practice and approaches to institutional capacity. However, we can already now present a couple of provisional conclusions:

First, it is methodologically intriguing that the planners’ reflections point at the fuzzy boundaries on what is internal (and ‘controllable’?) and external (and ‘out of reach’?) aspects or variables in scenario building around uncertainty issues. Is there a need for a conceptual approach which does not operate with the implicitly imposed boundaries of ‘internal’ and ‘external’, akin to the generalised symmetry proposed in actor-network theory?

Second, it seems as if policy labs have important learning and hence potentially transformative effects. Although continuity is required to enable the capacity building the approach promises as the impact is over a longer time and mainly seeds for change are sown.