I have been working as a researcher in sustainable transport and new technologies for the last seven years, and in the last couple of years I had the opportunity to work on research projects that explored the future of transport systems, including the role of digitalisation, new technologies and decarbonisation. I was therefore very excited when I was offered the opportunity to work in the Triple Access Planning (TAP) for Uncertain Futures project.

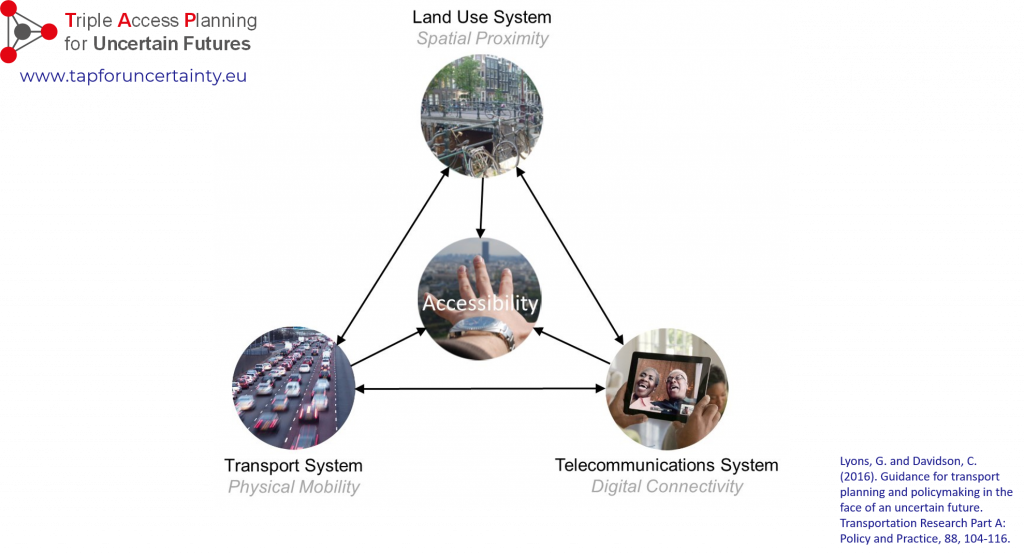

My first task as part of the research team at the University of the West of England (UK) was to design and develop a tool to support Triple Access Planning. I was told we were going to use System Thinking to better understand the interconnections affecting accessing access in urban areas between the Transport system and the Telecommunication and Land Use system. Therefore, I did some research to understand better what that meant in practice.

I asked myself: “What is a system?”, and I found a very nice definition by Donella Meadows, who says that a system is “a set of elements or parts interconnected in such a way that they produce their own pattern of behaviour over time”. I was quite happy with this definition, as I had been introduced to Transport Systems when I started my master’s in Transport Engineering, and I learned how a transport system and the internal relationships among its components can be dynamic, complex, and influenced by a series of internal and external factors (or systems). This might sound very complicated, but it is fundamental to understand how to design a better, more efficient, inclusive, and cleaner transport system in the future.

With system thinking I learned that it is possible to understand why and how systems behave the way they do, and how it can be used to communicate and share expertise with local experts and planners. Barry Richmond talked about “System thinking” already in 1987, suggesting it can be used to analyse and explain complex interdependencies. The literature does not provide a unique definition, but rather a range of different descriptions of what “system thinking” is, and this underlines its high complexity. To simplify it in a few words, we can say that it is a system of thinking about systems.

When we use system thinking, we need to consider:

- Elements, components, or variables, which characterise the system.

- Interconnections, relationships, or flows, between the elements, highlighting dependencies.

- A purpose, which is the most important thing we need to have clear when we decide to use system thinking, as this will guide us in understanding how the system behaves.

There are several tools that we can use to apply system thinking, including Network Analysis, System Dynamics, Logic Mapping, Viable System Mapping, Cognitive Mapping, Theory of Change, Soft Systems Methodology, Agent-Based Modelling, and Causal Loop Diagrams.

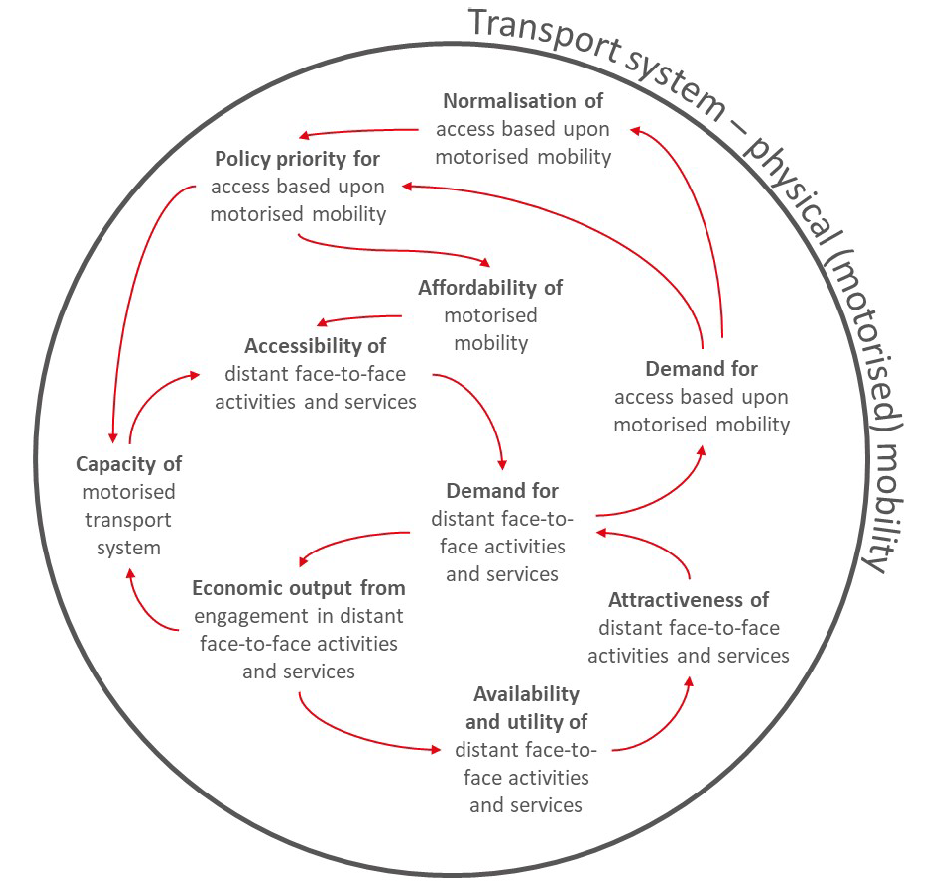

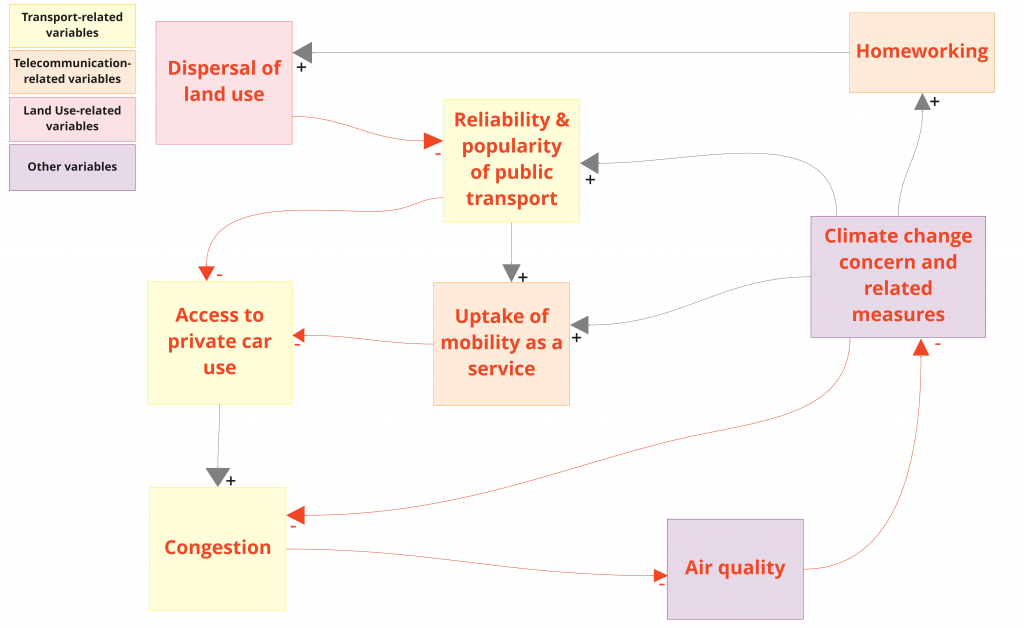

We wanted to co-design with the project partners (e.g., academics and practitioners) a system of systems that included the Transport System, the Telecommunication System and the Land Use System. Due to the nature of the research we decided to use the Causal Loop Diagram (CLD) method, as it is very helpful when you want to transfer and visualise the variables (and their relationships) that you already have in your mind in a diagram. CLDs use only two elements: variables (indicated with their names) and causal links (indicated by arrows). The (direct/indirect) nature of the relationships between variables is indicated by a positive or negative sign.

In addition, the CLD allows to identify feedback loops and priority areas where to start/focus and therefore design a strategy. We found that this is a very powerful tool when you want to work on system thinking with experts who speak different “languages” (e.g., academics, practitioners, transport planners and local authorities). This is why system thinking and CLDs can be used by practitioners and transport planners to explore how the bigger-picture dynamics can change when some parts of the system change.

Across five online multi-stakeholder workshops with the TAP partners we have considered a range of variables with different natures (e.g., Congestion, Land Use Diversity, Homeworking), all interconnected within the three sub systems (Transport, Telecommunication and Land Use) to compose the Triple Access System. System Thinking was completely new to most of the participants, so we ran a first workshop to allow them to familiarise with the concept. First reactions from some participants were something like “Why am I here?”, “What are they asking me to do?”, “I don’t feel I have the right expertise to do this”, and this is why having a well-designed whiteboard and a good moderator are crucial.

All things considered, I have gathered some tips to use System Thinking in the future:

- Identify stakeholders– including transport practitioners, city planners, local authorities and academics/experts. It does not matter if they have little (or no) experience in system thinking, as you will oversee the process, making them feel comfortable when you are running your workshop(s). It is important that they are varied and have a role in influencing the system.

- Think about access – not only transport issues and solutions. Transport is a derived demand, so we should move beyond ‘only considering transport solutions for transport problems’ and consider other additional solutions, as transport solutions may not be the only recourse to addressing transport problems. This include the strong link between transport and land use, but also other solutions within the broader concept of urban accessibility.

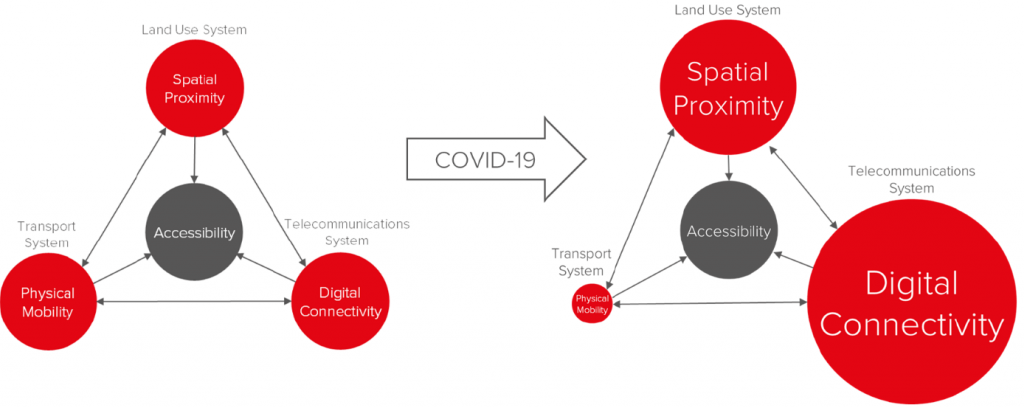

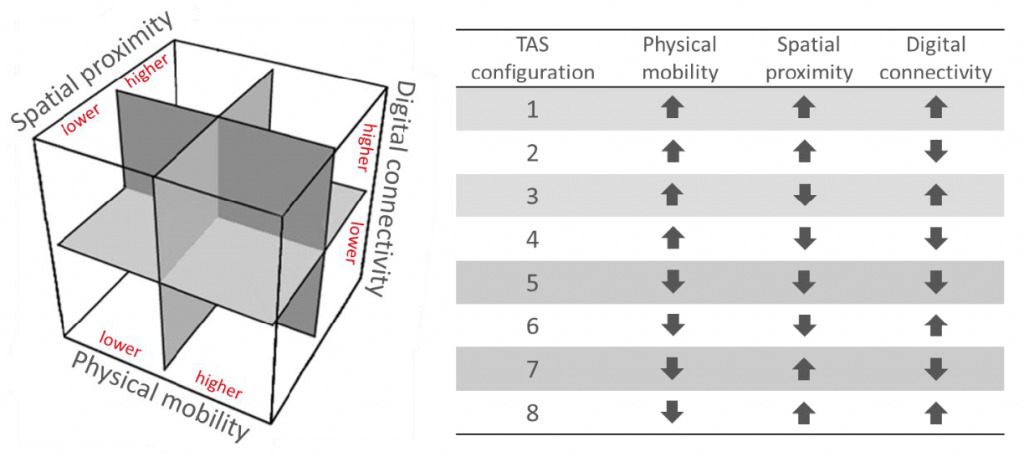

- Consider the key role of Digital Connectivity in the future of urban accessibility – especially with virtual mobility replacing physical mobility to fulfil urban access needs. This “third leg” has been largely ignored in transport planning so far, but it is increasingly finding its space in changing the way people access and move in an urban area.

- Think about the Triple Access System – try to understand how variables are related to each other and how the system behaves in order to design a sustainable urban mobility plan.

- Keep it simple – understandable by experts and non-experts, and easy to use – avoid ambiguity when you define a variable, which would only unnecessarily increase complexity, and try to keep simple relationships among variables, avoiding direct connections when indirect connections are possible.

- Be patient – take your time and do not feel rushed to find a conclusion quickly. TAP is an approach to visualise and communicate what our minds think urban accessibility is. It can therefore support researchers, practitioners and transport and city planners to better think what the system is, and at the same time to understand what implications a specific measure can have. It is therefore important to gather a good understanding of how the smaller issues/relationships/sub-components contribute to the bigger picture.

Thinking together added incredible value to our understanding of what Triple Access System means and how the sub-systems can interact to each other’s in a complex and uncertain future world.

I hope this post helped you understanding how the power of system thinking can support us in future transport planning. If you liked this post or have any questions/comments or other resources to share, please contact me at daniela.paddeu@uwe.ac.uk.

__

Daniela Paddeu is Senior Research Fellow in Transport Studies at UWE Bristol, and a member of the Triple Access Planning for Uncertain Futures project team.