By Daniela Paddeu, Glenn Lyons, and Kiron Chatterjee, UWE Bristol

Addressing global climate change is not just a stock phrase; it is a call to action that resonates deeply with the challenges and aspirations faced by urban mobility planners.

We interviewed 23 practitioners between September 2022 and February 2023 to understand their perspective on the past, the present, and the future of urban mobility in the UK. These were predominantly transport planners, with some spatial planners, and a few planners who were looking at the role of digital services. Although all involved in planning in their current work, they had a wide variety of educational backgrounds and experience. We used the ‘Seven Questions’ interview method, which is designed to be thought provoking and to allow interviewees flexibility in responding while taking them on a ‘thought journey’ between the past, present, and future.

What have we learned?

Exploring the perspectives of practitioners allowed us to identify some pathways to a vision of success for urban mobility planning. We identified key themes, including transport decarbonisation, accessibility to opportunities, travel behaviours, transport system characteristics, urban environment design, mindsets of the public and politicians, and governance and technical processes.

The urgent need to decarbonise transport, while providing equitable access.

Transport decarbonisation came out as a strong theme across all practitioners. It is not just about ‘hitting net-zero decarbonisation targets’. It is about understanding how to achieve ‘intelligent decarbonisation’. This means that we should promote more equitable and effective ways of encouraging active travel and placemaking to enhance local service accessibility. We need to provide evidence that sustainable measures produce environmental and social benefit, and we should engage with the public to increase acceptance of carbon reduction schemes. To do so, recognising that we need to overcome public reluctance and empower local authorities are crucial steps.

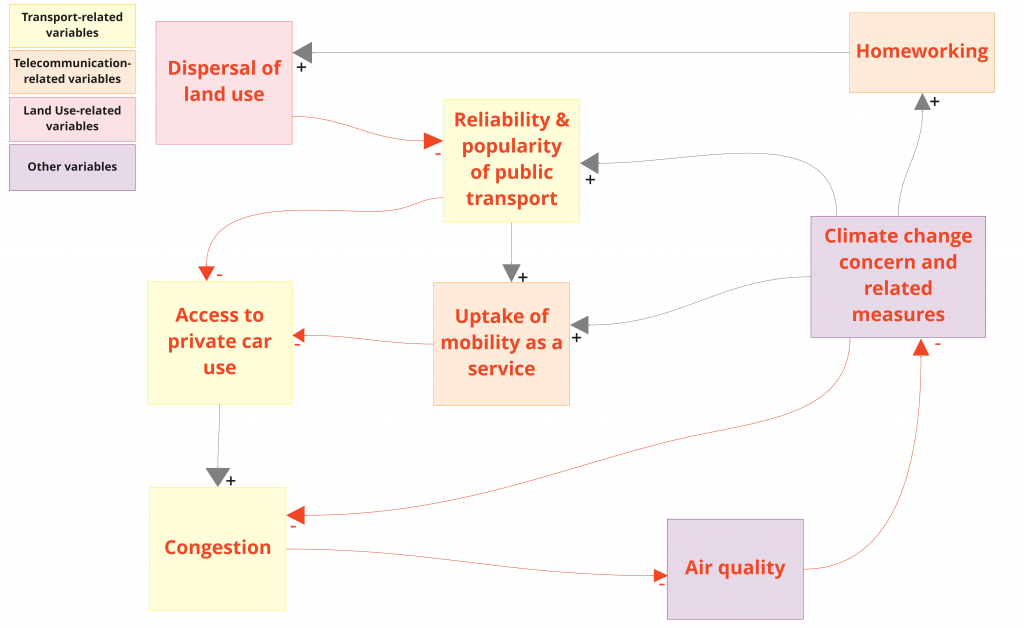

It is not only about decarbonisation though. Success in urban mobility planning should be measured by ensuring the population has sufficient accessibility to opportunities. This includes the need for transport to contribute to good quality, equitable access to goods, services, and opportunities. The Triple Access System concept, encompassing mobility, proximity, and digital access, was highlighted by practitioners as a valuable tool for prioritising areas in need of better accessibility.

The impact of digital access, accentuated by the rise in home working and online shopping during the Covid-19 pandemic, can be another key tool to increase urban accessibility. Reducing the need for travel, while enabling people to (virtually) undertake activities, will support transport decarbonisation, and increase urban accessibility. However, despite the importance of digital connectivity, physical mobility is still seen as playing a crucial role in people’s lives.

The vision of success among practitioners often focused on the need for a shift in travel behaviour and patterns, emphasising a reduction in car use and an increase in active travel and public transport. This would not only help achieve carbon reduction targets but also address other issues such as congestion, air quality, health, and liveability of urban areas. Modal shift can here play an important role. We will need to design appropriate and effective modal shift strategies. This can include, on the one hand, the adoption of a model hierarchy favouring pedestrians, cyclists, and public transport. On the other hand, we will need to understand how to reduce the use of car with stick measures (e.g., traffic restrictions) and explain what the social benefits are to the population. This could be accelerated by engaging with local developers to create low-car developments. An ideal transport system was described as one that offers a real choice of alternatives to the car, promoting multimodality, which will be enabled through the integration of various transport modes through concepts like Mobility as a Service.

The way we design our urban space to maximise access to places, goods, and opportunities.

Another important factor to achieve the success of urban mobility planning would be designing the urban environment in a way that limits the need to use motorised transport, as we can access everything we need walking or cycling (or online). We will need to create places that are liveable, walkable, and pleasant, where residents can meet most of their needs locally, reducing the need for private car ownership. The 20 Minute Neighbourhood concept was seen as being a powerful concept but will require improved road safety to support active travel. Success in urban mobility planning was described in terms of developments that prioritise safe walking and cycling.

It is rather unfortunate that the ‘20 Minute Neighbourhood’ concept has been weaponised as part of current so-called culture wars. A commonly mentioned necessity for change in our interviews was the transformation of mindsets among the public and politicians. It is important to win hearts and minds to encourage people to adapt and change their behaviours. To achieve this, communication, education, and changing the narrative to emphasise positive aspects and social benefits of sustainable transport are key. It is not just about the public. A change in the mindset of politicians is needed, whereby there is reduced influence of car drivers on political decisions. It becomes therefore important to improve consultation and to find new ways of engaging younger communities to achieve better public engagement.

Key take aways from the interviews

With this blog we wanted to share some insights from practitioners’ hopes and fears about achieving their vision of success for urban mobility planning. All the practitioners that we interviewed acknowledged that power in the UK is very centralised, and the relationship between central government and local government in decision-making processes and financial support are key threats to future success. There should be a greater devolution of power and funding to local governments, providing them with more autonomy to implement effective plans. In particular, longer-term funding settlements and improvements in the transport appraisal process could enhance the efficiency of local authorities in supporting public transport services. Cross-sector collaboration, a long-term perspective, appropriate funding, and political agency become essential for successful urban mobility planning.

The conversations we had with practitioners shed light on the multifaceted challenges and aspirations within urban mobility planning. The Sisyphean nature of urban mobility planning, coupled with new catalysts for change such as the climate emergency, deep uncertainty, and digital accessibility, presents both opportunities and challenges. This has been a deep learning experience for us, and we received a strong message about the need for collaborative efforts, a long-term perspective, effective communication, and a balance between technological innovation and evolutionary planning. As practitioners navigate the complex landscape of urban mobility planning, the blog calls for a collective effort to address the pressing issues and move towards a more sustainable and equitable future.