Many people across Europe and beyond now take for granted that the digital age is integral to their lives, offering the ability to reach people, goods, employment, services and opportunities through online facilities. Digital accessibility is happening all around us. Yet remarkably when we turn attention to transport planning, urban mobility planning in particular, we seem to largely if not entirely ignore how this will play a part in shaping the future of mobility – mobility derived from where, when and how people engage in economic and social activity.

The project Triple Access Planning for Uncertain Futures is focused upon how to rethink urban mobility planning through the lens of triple access – physical mobility, spatial proximity and digital connectivity – contributing to how people participate in society. On 23 June we ran a workshop with academics and practitioners within and beyond the project to explore the opportunity, but also challenge, of how to explicitly take advantage of digital accessibility within Sustainable Urban Mobility Plans (or ‘Local Transport Plans’ in England). After all, can we afford to ignore the role of digital accessibility when we are looking to transport in urban areas to rapidly reduce its carbon dioxide emissions?

In this article I draw upon the scene setting for the workshop I provided and the insights and conclusions from our discussions. Please share your own views – we all need to work on addressing this if we are to benefit from recasting transport planning as triple access planning.

Digital connectivity is a necessary but not sufficient condition for digital accessibility

There is an important distinction between digital connectivity and digital accessibility. I would explain them as follows. Digital connectivity reflects the availability of digital infrastructure and one or more devices (modes). Digital accessibility reflects being able to use digital connectivity to engage in activities. Digital connectivity is necessary but not sufficient to provide digital accessibility. The latter also relies upon the quality of digital services and digitally-enabled activities available (and affordable), and upon an individual’s competency and preferences when it comes to making use of what is on offer.

There is a complex and evolving set of relationships between digital accessibility and mobility

Pat Mokhtarian and Ilan Salomon have been pioneering scholars in trying to understand how use of telecommunications affects travel. In a 2015 paper called “Transport’s Digital Age Transition” I set out seven different relationships drawing upon Pat and Ilan’s work and that of my own and colleagues. Digital accessibility can:

- substitute for travel—an activity is undertaken without the individual needing to make a trip

- stimulate travel—information flows encourage the identification of activities and encounters at remote locations that individuals then choose to travel to (this can sometimes be a second order effect of substitution)

- supplement travel—increasing levels of access and social participation are experienced without increasing levels of travel

- redistribute travel—even if the amount of travel does not change at the level of the individual or at the aggregate, when and between which locations travel takes place can be changed

- improve the efficiency of travel—data and information flows can enhance the operation and use of the transport system (commonly considered under the heading of ‘intelligent transport systems’)

- enrich travel—whereby opportunities to make worthwhile use of time while travelling are enhanced, helping generate a “positive utility”

- indirectly affect travel—technologies can enable or encourage changes to social practices and locational decisions over time that in turn influence the nature and extent of travel

The problem is that within society and across individuals and their activities all of these relationships are at play. The relationships are also changing over time as digital connectivity and accessibility have evolved (dramatically). In 2000 the UK Government published its Ten Year Plan for transport. In this it observed that “[t]he likely effects of increasing internet use on transport and work patterns are still uncertain, but potentially profound, and will need to be monitored closely”. I wrote about this in my 2002 paper “INTERNET – Investigating New Technology’s Evolving Role, Nature and Effects on Transport” (good acronym, eh?!). Unfortunately, to my mind while the effects have proved to be profound, we didn’t really monitor them closely, or at least seek to make sense of them or what they might mean for transport planning.

Digital opportunities have grown considerably and permeated into our lives

It is worth reminding ourselves that while the transport sector often gets hyped up about revolutionary change that in practice seems slow to then materialise, the digital age has shown dramatic change. In 2000 just over of a quarter of the UK population had Internet access. But it wasn’t the access we know today that is heading towards Gigabit connectivity and 5G. It was access through a 56k modem. To have downloaded an HD movie (if the opportunity even existed) would have taken some 30 hours – yet 5G promises the opportunity to do that in a few seconds. Remarkable – so allow your imagination to contemplate what change we might see over the next 20 years, a period over which urban mobility plans being developed now may apply. How can we ignore digital accessibility in such plans?!

According to the Office for National Statistics, immediately before the COVID-19 pandemic, the following was observed in Britain:

- 96% of households had internet access

- 76% of adults had used internet banking

- 87% of adults had shopped online

- 18% of adults in Great Britain used internet-connected energy or lighting controls

And during 2019 in Britain (ONS):

- 87% of adults used the internet daily or almost every day

- the percentage of adults who make video or voice calls over the internet had more than trebled over the past decade reaching 50%

- 84% of adults had used the internet ‘on the go’

According to Ofcom, in 2020:

- the average time per adult spent online was 3.5 hours per day (excluding the average 1 hour 20 minutes also spent watching online services on TV sets)

- the NHS online service was used by 22.5 million UK adults in March 2020 as the country entered lockdown

Such statistics don’t seem particularly remarkable now – but imagine being presented with them in 2000 as a forecast of the future – it would have been possibly quite shocking, even moreso if someone had been able to explain the sophistication of the devices and services that would be available in 2022.

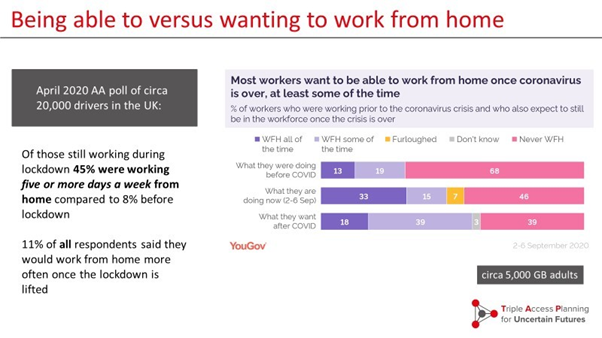

COVID-19 arrived and changed our lives forever, amplifying the place of digital accessibility

The world changed forever when the pandemic spread across the world. In 2019 it would have sounded far fetched to suggest huge parts of the workforce would be working from home full-time with business travel, especially international travel, replaced by online Teams and Zoom meetings, workshops and conferences. Yet now in 2022 we have become accustomed to this being part of working life, even if some are hankering after the ‘good old days’ of co-presence in the office and hypermobility in order to wheel and deal face-to-face in different parts of the country and beyond. What we are now being exposed to is coming to terms with the distinction between what we are able to do through digital accessibility versus what we want to do (or bosses want us to do). Surveys conducted during the pandemic offered some insights into how COVID-19 changed how we worked as well as what prospects in terms of preferences for future working practices.

Don’t be too quick to cast off digital accessibility as second best – it may be (becoming) superior

Of course some people will want to suggest that while digital accessibility was OK to rely upon during the pandemic, it wasn’t a match for face-to-face working. Well, this may be true for some people some of the time. But cast your mind back to some of the ‘old’ meetings you may have spent a good part of your working life attending. How productive were they really? Assuming suitable equipment and a suitable home office environment are available, ask yourself – isn’t the digitally accessible meeting sometimes, if not often, more flexible, productive, and perhaps even more engaging?

And if this is what digital working looks and feels like now, imagine how much more it might further evolve in the coming years and decades. How laughable it might seem that knowledge workers once trundled in metal boxes to ‘work factories’ and then trundled home again? Imagine if we were narrow minded enough to plan the future through only a transport lens.

The future is uncertain in terms of what forms digital accessibility will take

In 2010 I visited Hewlett Packard Laboratories next to my university campus to have a demonstration of their Halo videoconferencing facility. Complete with high quality screens, dedicated fibreoptic network connectivity and high-quality sound it was possible to create a boardroom for people near and far to be together. It seemed to me like a glimpse of the future – but one that might take some time to be available to the masses. Jump forward to 2022 and it’s quite different. So, is 2022 a good guide to digital connectivity and accessibility of the future, or will it be all change again? This is why accommodating uncertainty must also now be part of urban mobility planning, as well as thinking through a triple-access lens.

There are only weak signals about incorporating digital accessibility into urban mobility planning

While its plain that digital accessibility is here to stay and set to become an ever more integral part of our lives in the future, it’s far from clear that much if any attention is being paid to whether and how digital accessibility could be addressed in urban mobility planning. Perhaps transport planners have not seen it as part of their remit? Perhaps it had been put in the ‘too difficult box’? It is certainly true that it is very difficult to make sense of the systemic level of change attributable to digital accessibility change and take-up – and this may not change any time soon given the dynamics involved, the state of flux in society and the fact that making sense of digital accessibility is yet another wicked problem in society.

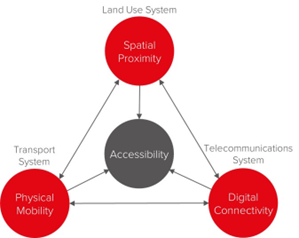

It is ironic, however, that transport planning orthodoxy seems to remain blissfully unaware of the complexity and dynamics of the Triple Access System – in which the transport system exists – as it merrily continues to put stock in road traffic forecasts and maintain a narrow lens focused primarily on the transport system, with some consideration of the land use system and virtually (ha, ha!) no consideration of the telecommunications system.

It may be important to apply how we judge mobility to how we judge digital accessibility

There are obvious parallels between the transport system and the telecommunications system: (i) roads provide the opportunity to move from one location to another, just as the Internet does; (ii) modes of transport provide the means of using the infrastructure, just as digital devices from smart phones to desktop PCs do; (iii) financial and educational means are needed to afford, and know how, to use modes of transport, as they are for digital devices; and (iv) movement between one location and another is derived from the appeal and suitability of the activities being reached, which applies whether these are face-to-face or digital remotely accessed activities.

When it comes to mobility, England’s National Travel Survey (in common with other such national surveys) refers to a series of journey purposes which in effect reflect the array of activities for which access is needed:

- Commuting

- Business

- Education

- Escort education

- Shopping

- Other escort

- Personal business

- Visiting friends at private home

- Visiting friends elsewhere

- Entertainment / public activity

- Sport: participate

- Holiday: base

- Day trip

For many of these it is apparent that digital accessibility now has a well-established place.

One can suggest that we should be asking ourselves in light of the comparison between mobility and digital accessibility, why aren’t transport planners doing more to incorporate digital connectivity (information and communications technologies – ICTs) and digital accessibility into our representation of behaviours we are looking to support and shape with our planning?

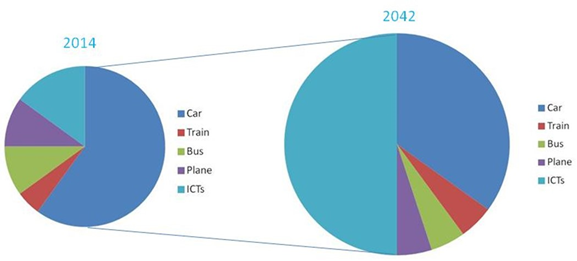

I prepared the diagram below (inspired by similar thinking from Pat Mokhtarian) in work I led for the New Zealand Ministry of Transport in 2014 when we conceived of the need for a ‘decide and provide’ paradigm in transport planning, centred upon the Triple Access System. It aims to remind us (as Pat’s work did) that we need to have in mind how the absolute amount of mobility (as Pat considered) and accessibility (as I’ve considered below by adding ICTs) and how the relative amount change over time. It is important for urban mobility planning to recognise that while society’s overall need for accessibility may grow over time, the same need not be true for physical mobility – especially motorised mobility. It is possible to conceive of maintaining or reducing motorised mobility while increasing overall accessibility. A neat example given in our workshop was how watching sporting events used to require physical presence at the venue whereas, thanks to television, such sporting events have been made accessible to countless millions as opposed to a few thousand.

Growth in digital accessibility has not been motivated by interest in travel demand management

It is possible to point to examples of where digital accessibility is helping to ease demands placed upon the transport system. Digital healthcare appointments are becoming more mainstream. Online grocery shopping of course still generates delivery trips but removes shoppers’ trips to retail centres. Digital meeting and workshop services and tools enable meetings to take place without travel. Broadband providers, offering digital connectivity, underpin all of this. However, such mechanisms have motives beyond an interest in helping ease pressure on the transport system (even if they have that motive at all). Often the motive is profit, service efficiency, economic prosperity etc. This is quite rational but it should not preclude recognising that in pursuing other motives, the consequence for transport planning of digital services provision can often be behaviour change dynamics that offer the possibility to reduce motorised transport. I say ‘possibility’ here because it depends upon how the benefits are locked in, such that motorised mobility does not pop up in other forms as a rebound effect. Sometimes at a local level, digitally-related services are indeed being provided with the direct interest in addressing people’s reliance on transport in mind – local co-working hubs being a good example. Indeed, for rural areas moreso than urban areas, such provision of support for digital accessibility may be more appropriate, cost-effective, and socially and economically beneficial compared to investment in the transport system itself.

Barriers to greater uptake of digital accessibility and reduction in motorised travel go beyond technology

For many middle-class knowledge workers it may seem rather intuitive and natural to turn attention to taking advantage of digital accessibility, as many did during the pandemic. However, for many others they may either not enjoy the availability of the same choice set for their behaviours, or may not be conscious of how their choice set has changed. If familiar behaviours continue to serve their purpose in a satisfactory way (e.g. driving to work) then habits can endure. Individuals become entrenched in particular patterns of behaviour. These are normalised socially for example in relation to the nature of work. It took the pandemic to really shake up the working world and expose many people to the unfamiliar but potentially eminently suitable and attractive option of working from home – an option that was in their choice set (employers’ and managers’ views permitting) they just hadn’t really considered it, or felt able to. For other people the technological means may not exist to be able to take advantage of some forms of digital accessibility. However, it may also be the case that they do have the technological means (or could afford to have it) but haven’t been afforded the digital literacy, skills and familiarity to be able to take advantage of the digital opportunities on offer.

Frankly, another obstacle to overcoming such issues as those above is that planners and policymakers are devoting far more attention to meeting people’s needs for access through physical mobility than they are through digital accessibility. In one of our European partner countries in our project it was suggested that there was a team in national government of around 100 professions working on digital developments compared to some 9000 working on transport developments.

We can embrace digital accessibility in urban mobility planning without fully understanding it

Exploring the prospects of digital accessibility, as noted above, can reveal it as a wicked problem in light of differences in interpretation, lack of evidence and understanding of cause and effect, and complex interactions that is has with other aspects of an urban system. It would be all too easy (especially with the ‘forecast-led’ predict and provide mindset in the transport sector) to forego a need to give serious attention to accounting for digital accessibility in urban mobility planning. This would be a grave mistake at this point in time – a point in time when we recognise the severity of the climate emergency and a need to rapidly decarbonise our economy, notably our transport system and its use.

Thankfully, the decide and provide paradigm is different – provided that its new philosophy – way of thinking – is embraced. This is about supply-led demand rather than demand-led supply. This was set out in my paper with Cody Davidson in 2016 – “Guidance for transport planning and policymaking in the face of an uncertain future”. We do not need to fully understand cause and effect, to be able to model the effects of change in supply on changing demand, in order to shape a better future. Consider this broad proposition:

- We need to create a sensible balance of physical mobility, spatial proximity and digital connectivity to meet society’s access needs while creating liveable places, assuring economic and social wellbeing and addressing climate change.

- Such balance is created by considering transport, land use and telecommunications supply.

- We may take a view that we do not need any more highway capacity for private cars than we already have.

- We may take a view in turn that any new infrastructure provision should focus upon supporting active travel and shared motorised transport, and that such new provision will come from some reallocation of roadspace away from the private car.

- We may then recognise the importance of ensuring everyone in society has a minimum level of opportunity to enjoy the benefits of digital accessibility which means addressing digital connectivity (and its affordability) as well as addressing digital literacy – and actively raising public awareness of the enriched choice set they can have at their disposal in terms of forms of access.

- We may assume that by determining a clear way forward for transport system capacity, and digital opportunity, that people and businesses will respond in an adaptive way in terms of locational decisions and wider behaviours (including innovations from transport service providers, digitally accessible service providers, and developers).

- In this way, the demand is left to respond to the supply on offer – choice remains but is bounded by supply-side system conditions.

- This is what the vision-led approach of decide and provide is all about – it is then important to continuously monitor how patterns of behaviour are changing and to be ready to adapt investments and interventions to help ensure fairness in overall accessibility provision and to help mitigate unanticipated and undesirable consequences.

This surely offers a proposition worthy of consideration in the times we are living in? Is it not a tempting foundation for improving urban mobility planning? If not, then what is the alternative because digital accessibility is increasingly pervasive in society and if planning is about shaping a system to be fit for the future it cannot do so in ignorance of the fundamental building blocks of that Triple Access System.

__

Glenn Lyons is the Mott MacDonald professor of future mobility at UWE Bristol, and the coordinator for the project Triple Access Planning for Uncertain Futures.